Modesty has never been one of New York City’s defining traits. Its bold and outgoing nature is what attracts tourists and residents alike. The iconic buildings, towering over streets and parks, are nothing short of remarkable. But, the city is asking many of these buildings, some nearly 100 years old, to change, and they haven’t been given much time to do it.

New York City has created an aggressive strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and is aiming to be a carbon-neutral city by 2050. In fact. Local Law 97, part of New York City’s Climate Mobilization Act, is one of the country’s boldest climate laws, with half a dozen other municipalities pursuing similar models. The end goal is great, but a lot of people, including condo owners and co-op members, are deeply concerned about how they will comply with the aggressive requirements.

Local Law 97 is intricate, and this article won’t cover everything, but you should be able to understand the basics, including who to contact if you need help, by the time you reach the last paragraph.

Table of contents

- What is Local Law 97?

- How is a building’s carbon footprint measured?

- How can a building lower carbon emissions?

- Paying for the costs

- Current obligations

- Exceptions

- Request for adjustments

- Fines and penalties

- Preparing for 2030; the next big milestone

What is Local Law 97?

Local Law 97 is far-reaching legislation aimed at making New York City a carbon-neutral environment by 2050. The comprehensive document is available here.

Since buildings account for approximately two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions in New York City, a plan needed to be constructed exclusively for them. Local Law 97 puts a cap on greenhouse gas emissions from big buildings, including condos and co-ops, and establishes methods for these buildings to support the law’s objective.

Local Law 97 was passed by City Council in April 2019 as part of former mayor Bill de Blasio’s Green New Deal. The Law became effective in November of 2019.

The square footage of a building, as it appears in the records of the Department of Finance, determines whether a building may be subject to Local Law 97.

The most pressing item for co-ops and condos is to confirm whether they are subject to the law. Every board should know this by now, but there is a searchable list of all of the buildings covered under the law.

Your building is likely required to comply with Local Law 97 if:

- It exceeds 25,000 gross square feet

- There are two or more buildings on the same tax lot that together exceed 50,000 square feet, or

- There are two or more condominium buildings governed by the same board of managers and together, the buildings exceed 50,000 square feet

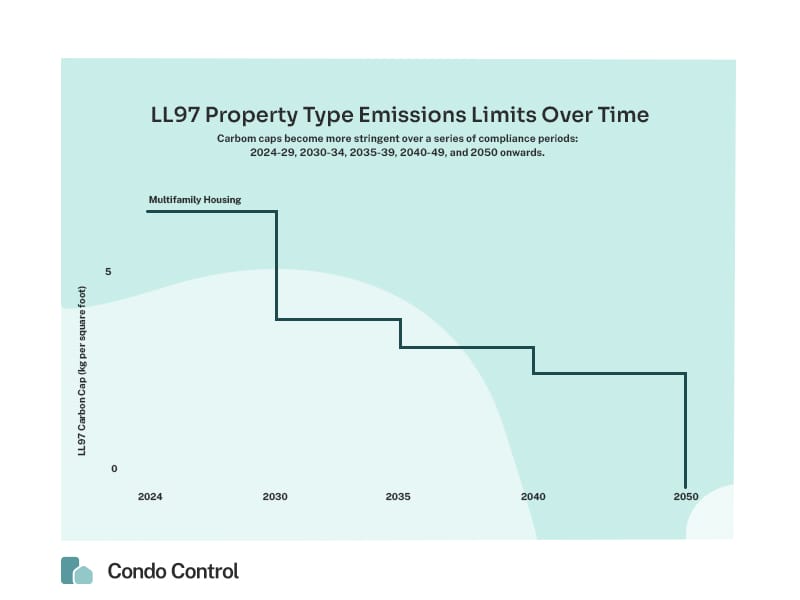

There are a series of benchmarks that qualifying buildings need to meet. The first is set for 2025, but it is estimated that only about 10% of buildings will need to take significant actions to reduce emissions. A greater percentage of buildings will need to reduce emissions to meet the 2030 benchmark, though. By that time, New York wants to have cut carbon emissions from buildings by 40%.

Source: Urban Green Council

Also starting in 2025, in addition to meeting the first benchmark, building owners/ board members will have to submit an annual report by May 1 summarizing their carbon emissions for the previous calendar year. The board must use the Energy Star Portfolio Manager to benchmark and report usage data, but the report must be verified by a registered design professional first.

If a complete report is not submitted, there will be serious fines issued to the building owner or board.

How is a building’s carbon footprint measured?

Local Law 97 establishes a building’s carbon footprint based on:

- Its Scope 1 – onsite combustion

- Its Scope 2 – purchased energy, such as electricity or steam, emissions

These totals are converted by energy type into their carbon equivalent (or CO2e). The type and size of the building also factor into the equation.

The law assigns a carbon coefficient to specify the carbon content for each fuel type. A building’s annual emissions are determined by combining total energy use for each fuel type, multiplied by its corresponding carbon coefficient.

The fuel type measurement is what’s causing concern for boards. New York is full of pre-war residential buildings. These gorgeous buildings are characterized by their brick walls, high ceilings and wood floors. Even though these masterpieces are sturdy, they aren’t exactly energy efficient.

Many condos and co-ops use fossil fuels such as natural gas for heat and hot water, but this type of fuel will certainly push a building above its emissions limit.

Residential communities are given a tough choice; maintain current energy systems and pay thousands of dollars in fines every year, or pay millions to replace old systems with more energy-efficient equipment.

People are worried that no matter what direction the board takes, they won’t be able to afford more expensive maintenance fees or exorbitant special assessments.

There is a bit of good news though. There are programs that can help offset the sting from the costs associated with going green.

How can a building lower carbon emissions?

Condos and co-ops first need to know how much energy they are using. They should start with the Energy Star Portfolio Manager benchmarking tool and work with a certified architect or energy consultant to determine the building’s energy usage.

The next step would be to identify the best methods for reducing emissions. Simpler actions include switching lightbulbs for LEDs, using sensory technology so that lights in common areas aren’t always on, and replacing windows that let in heat and cold (note that buildings in historic districts probably require extra approvals if changes are made to the windows or façade).

Replacing boilers with electric heat pumps will be a much bigger investment, but a key step for many older condos and co-ops that need to lower carbon emissions. Others might need to rewire electricity to meet the 2030 standards.

In lieu of upgrades, some buildings are at least considering alternative technologies that limit emissions but don’t eliminate the building’s reliance on fossil fuels. Carbon capture is one example. The New York Times published a story featuring a 30-story apartment tower in Manhattan that is capturing carbon dioxide from its gas boilers, cooling it to a liquid, and trucking it out to a concrete factory in Brooklyn. Emissions are sealed into concrete blocks once they reach the factory. This type of solution has not been officially sanctioned by Local Law 97 though, so it would be wise to consult with an attorney before your community tries something like this.

Equipment leases can also be more affordable, but they are not long-term fixes. Traditionally, these types of leases have been used for laundry rooms, but some communities may be able to rent solar panels to offset energy usage.

Paying for the costs

The costs associated with reducing carbon emissions are not cheap. Anyone involved with Local Law 97 will readily admit that it’s a tough initiative.

Traditional financing methods include allocating costs to maintenance or common charges, levying special assessments, taking money from cash reserves, and taking out loans.

All of these options have advantages and disadvantages, but in each scenario, the owners are the ones footing the bill.

Another solution is for a board to identify a “preferred lender” willing to prequalify a building and offer home equity lines of credit (HELOC) to shareholders or owners who prefer to finance their obligations.

There are also incentive programs offered by utility companies like Con Edison and National Grid, as well as state programs through the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. Con Edison offers free LEDs and low-flow devices for eligible building residents, and if your building is in Brooklyn or Queens, you may qualify for special offers and free energy efficiency upgrades through the provider’s neighborhood program.

Communities that are feeling overwhelmed are strongly encouraged to reach out to the Sustainability Help Center, or NYC Accelerator for free one-on-one guidance.

NYC Accelerator may connect you with the New York City Energy Efficiency Corporation (NYCEEC), a non-profit that helps finance clean energy projects and reduce carbon emissions. While there are no guarantees, the NYCEEC offers a generous Multifamily Express Green loan which covers up to 90% of proposed clean-energy projects. The minimum loan for co-op and condo boards is $200,000, and qualifying projects include HVAC upgrades, electrification, and building envelope upgrades.

Finally, your building might be exempt from meeting early benchmarks. We will look at exceptions after the next paragraph.

Current obligations

As stated earlier, 2024 is primarily for figuring out how much energy your building is using, and whether you need to do anything in order to meet Local Law 97’s 2025 standards.

Every building required to follow Local Law 97 must also submit its 2024 building emissions report by May 1, 2025.

It’s also the due date for decarbonization plans. While condos and co-ops shouldn’t plan on missing benchmark goals, they have been given a little bit of wiggle room.

Boards can receive an extension to comply with the 2024 emissions limit until 2026, so long as they demonstrate “good faith efforts” in decarbonizing their buildings. What exactly does that mean?

Even if they don’t have the money to make big changes this year, condos and co-ops that may not meet the 2025 target must demonstrate that they are doing everything they can to reduce emissions. That includes submitting a decarbonization plan, which must be certified by a registered design professional and includes an energy audit that is no more than four years old, to the Department of Buildings. The plan must demonstrate how the building will achieve on-site emissions reductions by 2026.

Another option is for boards to provide evidence that a complete application has been approved by the Department of Buildings (DOB) for the work necessary to comply with the first reporting limit, a timeline for completing the project, and an estimate of total emissions reductions achieved after the work is complete. If the work doesn’t require an application with the DOB, a signed contract with the service provider performing the work, and proof of payment, can be submitted instead.

Alternatively, subject to certain conditions, buildings may be able to purchase Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) to meet their emissions targets. However, a condo or co-op could not submit a decarbonization plan and also purchase RECs to offset emissions that exceed the limits imposed by the first five-year reporting cycle.

Finally, May 1, 2025, is the date by which most covered rent-regulated buildings and houses of worship have to submit a report showing they’ve complied with the requirement to implement energy conservation measures.

Exceptions

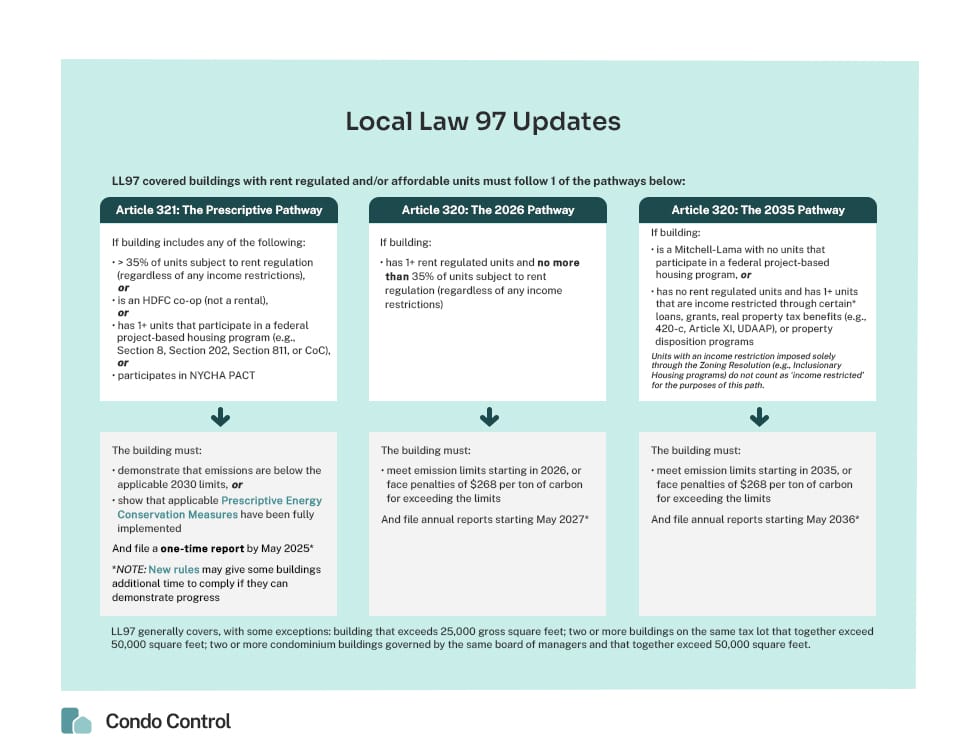

Yes, affordable and rent-regulated housing are afforded some special treatment given their limited resources, but they are not exempt from the requirements of Local Law 97. Instead, they must determine which of the two articles that make up the law as outlined in Title 28 of the NYC Administrative Code apply to them:

- Article 320 establishes Building Energy and Emissions Limits for buildings starting in 2024 and outlines the implementation of such limits

- Article 321 establishes Energy Conservation Requirements for Certain Buildings that are not covered under Article 320

Under Article 320

Buildings with at least one rent-regulated unit, and where up to 35% of units are rent regulated, may delay compliance with Article 320 emissions limits until 2026, and then must meet subsequent limits starting in 2030.

Under Article 321

Where the board chooses to follow the Prescriptive Energy Conservation Measures path, the following must be fully implemented no later than December 31, 2024:

- Adjust temperature set points for heat and hot water to reflect appropriate space occupancy and facility requirements

- Repair all heating system leaks

- Maintain the building’s heating system, including but not limited to, ensuring that system component parts are clean and in good operating condition

- Install individual temperature controls or insulated radiator enclosures with temperature controls on all radiators

- Insulate all pipes for heating and/or hot water

- Insulate the steam system condensate tank or water tank

- Install indoor and outdoor heating system sensors and boiler controls to allow for proper set points

- Replace or repair all steam traps such that all are in working order

- Install or upgrade steam system master venting at the ends of mains, large horizontal pipes, and tops of risers, vertical pipes branching off a main

- Upgrade lighting to comply with the standards for new systems set forth in section 805 of the New York City Energy Conservation Code, and/or applicable standards referenced in such energy code on or prior to December 31, 2024

- Weatherize and air seal where appropriate, including windows and ductwork, with a focus on whole-building insulation

- Install timers on exhaust fans

- Install radiant barriers behind all radiators

Rent-regulated buildings are by no means given a free pass, but the work they are being asked to do over the next few years is not quite as intense.

Request for adjustments

All condos and co-ops will be allowed to submit requests for adjustments to their building emissions limits under Local Law 97 if they believe there are valid or necessary reasons for exceeding the emissions limits. Applications must be sent to the Department of Buildings, and are due January 1, 2025.

Special circumstances may include, but are not limited to:

- 24-hour operations

- Operations critical to human health and safety

- High-density occupancy

- Energy-intensive communications technologies or operations

- Energy-intensive industrial processes typically classified as an unregulated load under the Energy Code

Fines and penalties

The fines for exceeding emission limits are significant and will add up quickly. Buildings will be charged $268 for every ton of CO2 beyond their limit.

Additional fines will be issued if the Department of Buildings does not receive an annual report, or if it receives a false report.

Condos and co-ops will be charged $0.50 per building square foot, per month, for failing to file a report.

Falsifying a report can cost a building up to $500,000, so boards shouldn’t even think about doing that.

There is a $10,000 fine for buildings that fall under Article 321 if they do not file their 2024 emissions reports by May 1, 2025, and a $10,000 fine for buildings that decide to complete the Prescriptive Energy Conservation Measures method but fail to document timely compliance.

Condos and co-ops that can demonstrate that they are doing all that they can to comply with Local Law 97 may be spared some or all emissions fines if they cannot meet their 2025 target. Being proactive and reaching out to the Sustainability Help Center or NYC Accelerator is always advisable if you are worried that your building will be hit with hefty fines.

Preparing for 2030; the next big milestone

As mentioned previously, roughly 10% of properties will surpass 2024 emissions caps, but that number could balloon to 65% of properties when the 2030 benchmark comes into effect.

New York anticipates a 50% reduction in emissions from 2006, which means buildings will have a more difficult target to meet.

The stricter emissions limits will require more buildings to fund and complete big projects in a short amount of time. Condos and co-ops need to design realistic plans that will demonstrate their commitment to Local Law 97 from now until 2050.

Conclusion

Reducing emissions isn’t going to be easy or cheap for most condos and co-ops. Local Law 97 is asking these communities to do a lot, and not every building will be able to hit the targets made for them.

Boards must take the law seriously, but they should also remember that perfection isn’t the goal. Rather, progress is what is most important. Furthermore, they should not try to do everything by themselves. Local Law 97 is a huge undertaking, and it’s going to take serious teamwork to get the job done.